Luca, Replacing Representation with Authenticity

Theatrical release poster for “Luca.”

Tricky, elusive, an ever-moving target, and an aerial acrobatics routine in which there is no safety net, but instead a kiddie pool filled with sharks. I am referring hyperbolically for the sake of comedic effect to the cultural conversation around representation in media. When I say “representation in media,” I mean characterized portrayals of fictional persons who identify with a marginalized or otherwise underrepresented group. And, when I imply how tricky it can be to discuss such issues, I just mean that it can be really, really tricky to discuss such issues.

That’s not to suggest that I think that these types of conversations, and the qualities of specificity and nuance required to partake in one, are inherently a bad thing. In fact, I feel the opposite. These days, I often find myself exhausted by the line of thinking which suggests that “the pendulum has swung too far the other way” towards social justice and political correctness, making these types of conversations unsustainable and achingly one-sided.

On the contrary, I’d argue that nuance and particularity makes our society more refined and inclusive, and ultimately pushes us towards a more expansive cultural zeitgeist. Furthermore, most of the people who take this pendulous viewpoint (and never seem to stop talking about their fear of political correctness) aren’t relevant enough in my book to be canceled anyway. So relax beleaguered cultural commentators who fear “cancelation” as acutely as a child’s fear of the boogeyman, you’re safe in obscurity.

That said, the cultural conversation around what makes representation in media good or bad always seems to be a target in motion, and one that’s very hard to hit dead center. Most people have different lines to be crossed, and their own set of metrics by which to judge. Now, I live in Los Angeles, and unlike the water here, there never seems to be a drought of unsolicited takes on representation in media amongst Angelenos.

However, in combing through different opinions on representation over the years, it seems to me that no such media conglomerate or other corporate entity has come under fire as often as the Walt Disney Company has in recent years, particularly for their representation of LGBT characters.

In fact, they’ve been in line for the firing squad so many times, that their repeated press pushes for their “First Openly Gay Character” upwards of 10 separate times has been mocked so much that it’s become an open joke amongst cultural commentators, particularly queer ones. And, as someone who finds this trend as distasteful as medical-grade mouthwash, I’m delighted whenever these jokes emerge, namely, each time Disney presents yet another first openly gay stereotype they have the nerve to call “a character.”

It’s a running gag at this point amongst gay people that these crumbs of representation offered up by the Walt Disney Co. mean nothing to us as a community, are almost always in bad taste, and are perhaps more palatable for pseudo-progressive heterosexual audiences than for actual queer ones. Ultimately, it’s little more than pandering, and we can smell tactless pandering at the same distance from which we can smell awards buzz for middle-aged, prestige actresses.

However, there has been one recent entry into this cluttered foray of LGBT representation that I’d like to recognize as a surprisingly pacifying force for queer representation, rather than an incendiary one. Its emergence was subtle, and understated, and its power comes from the fact that it actually subverts this issue of representation entirely, while somehow creating the most affirming artistic statement regarding queer storytelling I’ve seen in years.

From Top to Bottom: Giulia (Emma Berman), Luca (Jacob Tremblay), and Alberto (Jack Dylan Grazer) scooter around the fictional Italian town of Portorosso.

I’m talking about Pixar’s latest film Luca, the story of two young sea monsters who masquerade as human children in the fictional Italian fishing village of Portorosso. Alberto and Luca, the two sea monsters in question, each have aspirations of living amongst the humans, Alberto being the self-proclaimed expert in human culture, as well as self-appointed mentor to Luca, who is otherwise naive to the ways of the surface.

Throughout the film, the two of them must hide their identities as sea monsters by staying out of reach of water. If they come into contact with even the smallest droplet of moisture, the point of contact will transform them back into their scaly, slimy, aquatic form, thus exposing them for the interlopers they are in a town that makes no secret of its hatred for sea monsters.

As a queer person, I found it easy to read the film’s subtext for themes that often resonate with LGBT audiences. At the very least, a story that revolves around hidden identity, and a world that doesn’t understand otherness, reads relatively queer no matter the specifics of the circumstances. But, if that wasn’t enough, Luca also explores themes of found family, coming of age, latent sexuality, jealousy, love, self-hatred, and acceptance; all themes that most queer people can relate to and identify with in their own lives.

However, the interesting thing about Luca, all its other fine qualities aside, is that there is actually no outright representation of LGBT people. None of the supporting cast, nor Alberto or Luca, are definitively labeled as queer, gay, lesbian, bisexual, or otherwise non-heterosexual. And yet, despite its complete lack of representation, to me, Luca is the best queer film I’ve seen in years. Its thematic resonance with me, a gay person, felt authentic and grounded in a way even more explicitly queer films (Call Me By Your Name and Love, Simon come to mind) sometimes don’t.

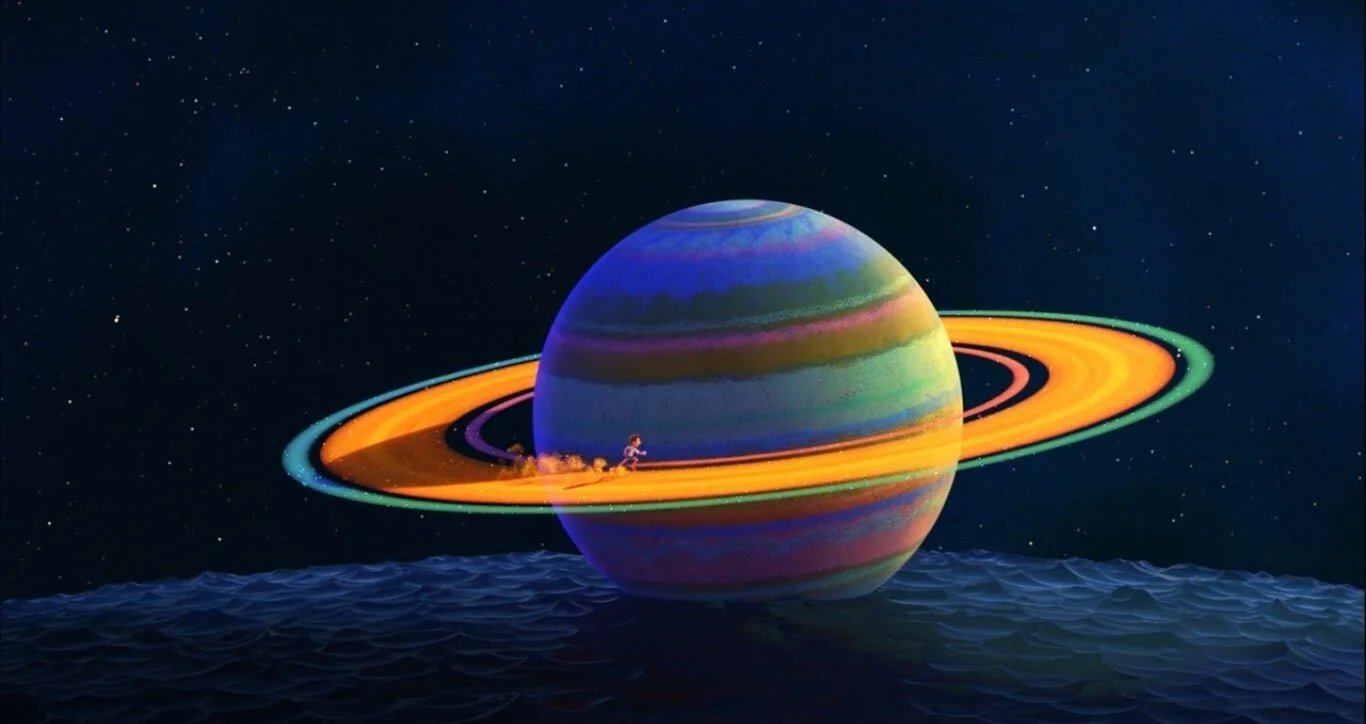

Luca daydreams about the Solar System, and the breadth of human scientific discovery.

I mentioned earlier that queer people, in my opinion, have an innate resistance to pandering. We can smell bad representation and inauthentic gestures from a mile away, and films like Call Me By Your Name and Love, Simon (which each have their own debatable merits) cannot always avoid the novelty of being marketed specifically for queer people in a way that can feel disingenuous. Not to suggest that these films don’t also have many fine qualities between them, but sometimes, particularly in the realm of casting, these movies can suffer from mixed messaging when it comes to representation.

I recently made a similar argument about the film Hedwig and the Angry inch, which alludes to this contrast between marketability and queerness. I won’t go into the details again regarding this paradox of popularity and queerness (mostly because you can track Neil Patrick Harris’s declining IMDB STARmeter on your own time), but in this previous post, I offer up the argument that mass appeal and queerness sometimes work against each other.

And to me, that issue spills over into queer representation as well.

So, the question becomes, how do you avoid this issue of explicit queer representation feeling occasionally like pandering while also telling stories that matter to queer audiences?

Alberto and Luca in sea monster form.

Luca is the solution. I would argue that its authenticity and thematic resonance with queer audiences bridges the gap between the need for LGBT people to see themselves on screen (the majority’s offered argument for why representation matters) and the elusiveness of tactful queer representation in mainstream media.

In fact, it seems once you remove the need for explicit representation as Luca does, it opens up the path for elements of artistry that engage audiences the most: allegory, symbolism, metaphor, etc. These elements make us, as audience members, read the text of a film through the lens of our perspective, imprinting our queer experiences onto the layers of a movie’s plot, characters, and the like. We interact more thoroughly with the art, rather than have the art spoon-feed us lazy representation. And ultimately, it seems this spoon-feeding is the methodology that gives us Disney’s seventh or eighth “first” gay character, and leaves us with a bad, medicinal taste in our mouths.

To me, Luca is not only the argument for the relevance of queer storytelling, but also the argument for the irrelevance of explicit representation. Its relevance also raises important questions.

Is it necessary for queer stories to also make explicit work of “otherness” and non-conformity by hyperfixating on sexual labeling or identity? Does that hyperfixation in fact dwarf or minimize otherwise artful means of expression, like allegory (what some would occasionally call coding) or metaphor? Alternatively, is it enough to tell a story of authentic queeress, whether intentional or not, that resonates with LGBT audiences, and let us determine what makes a piece of art representative of us as whole, or as individuals?

I would argue the latter, as I would much rather determine for myself what makes a piece of art representative of queerness, rather than have a plethora of think pieces and corporate press releases tell me in an attempt to garner progressive clout with audiences.

Perhaps, if the pendulum has swung too far one way, it may be in our attempted deification of representation over authenticity and artistry.

Luca is available to stream on Disney+.